10 common misconceptions about the public domain.

Do you know what “in the public domain” means?

Judging from questions I’ve gotten (and statements I’ve read elsewhere) it’s clear that there are some misconceptions about the public domain floating around the interwebs.

So I thought I’d round up a few. Like, oh, I don’t know, ten.

Here they are ...

How many of these statements do you believe?

- If a work is within the scope of most people’s general knowledge it’s in the public domain.

- Anything I find on the Internet is in the public domain.

- If a work doesn’t have a copyright notice on it, it’s in the public domain.

- If a work has a copyright notice on it, it’s not in the public domain.

- If I republish or repackage a public domain work, I can claim copyright in it.

- Posting a video to YouTube puts it in the public domain.

- Books that are out of print are in the public domain.

- All US government works are in the public domain.

- Statues and other art works on federal property are in the public domain.

- If a work is in the public domain I don't need to get permission from anyone, no matter how I want to use it.

Note: Remember, this site is about the public domain in the United States.

1. If a work is within the scope of most people’s general knowledge (that is, it’s well known), it’s in the public domain.

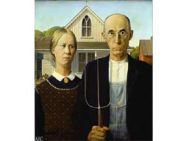

American Gothic (1930), oil on beaverboard, 74.3 x 62.4 cm. All rights reserved by The Art Institute of Chicago and VAGA, New York, NY.

In the context of copyright law the term public domain has a specific legal meaning. It means a work is not protected by copyright. The mere fact that a painting, say, or any other type of creative work, is well known does not place it in the public domain.

For example, Grant Wood’s painting, American Gothic, is one of the most famous paintings in American art history, but its copyright status is a matter of disagreement.

The copyright in a work of art created in 1930 had to be renewed in 1958 (see more info about copyright renewal here). There is no indication that Wood or the Art Institute of Chicago (to whom he sold the painting) renewed the copyright. But Nan Wood Graham, the artist’s sister and the model for the woman in the painting, registered a reproduction of American Gothic in 1952 and renewed the copyright in 1980.

Whether you believe Nan’s registration and renewal saved the copyright in this iconic image or not, the Visual Artists and Galleries Association (VAGA) oversees commercial uses of Grant Wood’s work, and you had better believe you’ll be dealing with VAGA if VAGA believes you need copyright clearance.

2. Anything I find on the Internet is in the public domain.

Since we’ve been awash in Internet-related copyright litigation for some time now (remember Napster? heard about those RIAA file-sharing lawsuits?) I’m surprised people still believe this. But they do.

Yes, there are public domain works on the Internet (this site helps you find them), but the reason those works are in the public domain has nothing to do with the fact that they’re on the Internet. They are in the public domain because they’re not protected by copyright — not because copying them is as easy as right clicking your mouse.

The fact that something is posted on the Internet does not give you or me the right to copy and distribute it freely. Unless a work’s creator expressly gives up his or her rights, those right are reserved. If you use a copyrighted work without permission and your use doesn’t qualify as a fair use, that’s copyright infringement.

3. If a work doesn’t have a copyright notice on it, it’s in the public domain.

Not necessarily. Copyright notices have been optional since March 1, 1989, when the US joined the Berne Convention. Under the current Copyright Act, copyright protection is automatic. As soon as a work is “fixed in a tangible medium of expression” (written down, recorded, painted, etc.) it’s protected. No notice is required.

So if the work was created after March 1, 1989, it’s definitely protected by copyright — with or without a notice — unless the owner has given up his or her rights. If the work was created before March 1, 1989 and doesn’t have a copyright notice on it, it may or may not be protected. Why? If it was published without a copyright notice before March 1, 1989, the copyright might still be valid. You would need to do a bit of research to be certain of the work’s copyright status.

4. If a work has a copyright notice on it, it’s not in the public domain.

It still might be in the public domain. How? There are two ways. First, if the work was published in the US during the years 1923 through 1963, the copyright had to be renewed 28 years later or the work entered the public domain. The copyrights for many works were not renewed. You would need to check copyright renewal records to be sure.

Second, the copyright notice might be a fraudulent. False copyright claims are all too common these days, unfortunately. Many organizations such as music publishers, book publishers, and museums put copyright notices on reprints and photographic reproductions of public domain works.

So remember, just as the absence of a copyright notice doesn’t necessarily mean a work is in the public domain, the presence a copyright notice doesn’t necessarily mean the work is protected by copyright.

5. If I republish or repackage a public domain work, I can claim copyright in it.

There is a limit to what you can copyright in this case. When you add your own stuff to a public domain work, only the stuff you add may be protected by copyright. And then only if it meets the law’s originality and creativity requirements.

It’s misleading to say that you can “protect your public domain project from being stolen, with full legal protection,” as I’ve seen one Internet marketing “guru” do. Why? Because the underlying work will always be in the public domain. If a work is in the public domain you cannot claim a copyright in it. If you made a CD or DVD (or whatever) from it ... so can others. Not only that, but they’re free to do a better job, or add more value, or sell their product for less. Period.

6. Posting a video to YouTube puts it in the public domain.

No, it doesn’t. People seem to think that because the public can access videos on YouTube, for free, the vids are in the public domain. (I suppose this follows from the “everything on the Internet is public domain” misconception.) They’re in a public space, true, and people don’t have to pay to see them, but that doesn’t affect copyright.

You do in fact retain copyright in your video when you post it to YouTube (that would be your video, not your Stephen Colbert clip). But by posting it you grant YouTube a license to do pretty much whatever it wants with your work. That includes sublicensing it to others and modifying it (making derivative works). The license terminates within “a commercially reasonable time” once you remove your work from the YouTube site. And you still own the copyright.

7. Books that are out of print are in the public domain.

Not necessarily. Out of print doesn’t mean the book’s copyright has expired. Copyright protection lasts for a certain term whether or not the work is in print and being sold. Rights under copyright law aren’t like trademark rights, which depend on continuous use in commerce. Unless the copyright owner has clearly and unambiguously given up copyright protection, the work is protected for the duration of its copyright term whether it’s in print or not.

8. All US government works are in the public domain.

The key word in this misconception is “all.” Works created by US government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. Absolutely. But don’t assume that all US government works are. If the government hires an independent contractor to create a work for it, that independent contractor may retain copyright. Not only that, but some government organizations like the Smithsonian Institution and the US Postal Service can, and do, claim copyright in their works.

9. Statues and other art works on federal property are in the public domain.

Not necessarily. Ownership of the work itself (the statue or painting, etc.) and ownership of the copyright in the work aren’t the same thing. Here’s an example. The US government owns the Vietnam Women’s Memorial (the sculpture itself) and the work is on federal property, but the government does not own the copyright.

The Vietnam Women’s Memorial Foundation owns the copyright. The artist, Glenna Goodacre, transferred the copyright to the Foundation’s predecessor, the Vietnam Women’s Memorial Project, Inc., in 1993. So, if you wanted to make commercial use of the sculpture (say, selling photos of it or putting its image on coffee mugs) you’d have to get permission.

10. If a work is in the public domain I don’t need to get permission from anyone, no matter how I want to use it.

You might need permission. Most works in the public domain really and truly are free for you to use. But here’s the catch: the subject of the work and the way you use it could matter. If you intend to make commercial use of a public domain work that has a recognizable person as its subject, you’d best avoid violating their rights of publicity and privacy.

Also, some public domain art works may be protected as trademarks, or include trademarks. Although a fairly recent Supreme Court case ![]() limited the extent to which trademark law can be used to restrict the use of works in the public domain, you would be well advised to steer clear of using the work as a trademark.

limited the extent to which trademark law can be used to restrict the use of works in the public domain, you would be well advised to steer clear of using the work as a trademark.

There’s one more thing to watch out for here. If the work in question is a sound recording, even if it’s in the public domain outside the US it can (and probably will) be protected under state laws here.